By Doug Lefler

Bryn was gone for more than a week.

“King Edryd wants me to perform for him?” the young man asked the emissary.

They were standing to the side of the raised platform that served as a stage. The crowds were dispersing, but the clapping and shouting from the audience still reverberated in Bryn’s head. The Festival of Enlightenment had been a brilliant success for him. Although each morning when he woke, he thought of Modesty, the sound of applause had not lost its hold on Bryn. He was chained to two oxen, each pulling him in a different direction, and he could not tell which force was dominant.

“Our Majesty commands a performance next Friday, in the Great Hall of Ironhorn.” The emissary wore robes dyed a rich purple. It was a color the common folk could not afford. “Can I assure him that you will oblige?”

Bryn was a quick young man and could have manufactured devices to evade this request, but perhaps we can forgive him that he did not. He was a musician by trade, and this was a command performance for the King of Ironhorn.

“The King would like to hear one song in particular,” the emissary said as he turned to leave. “‘Lady of the Trees’.”

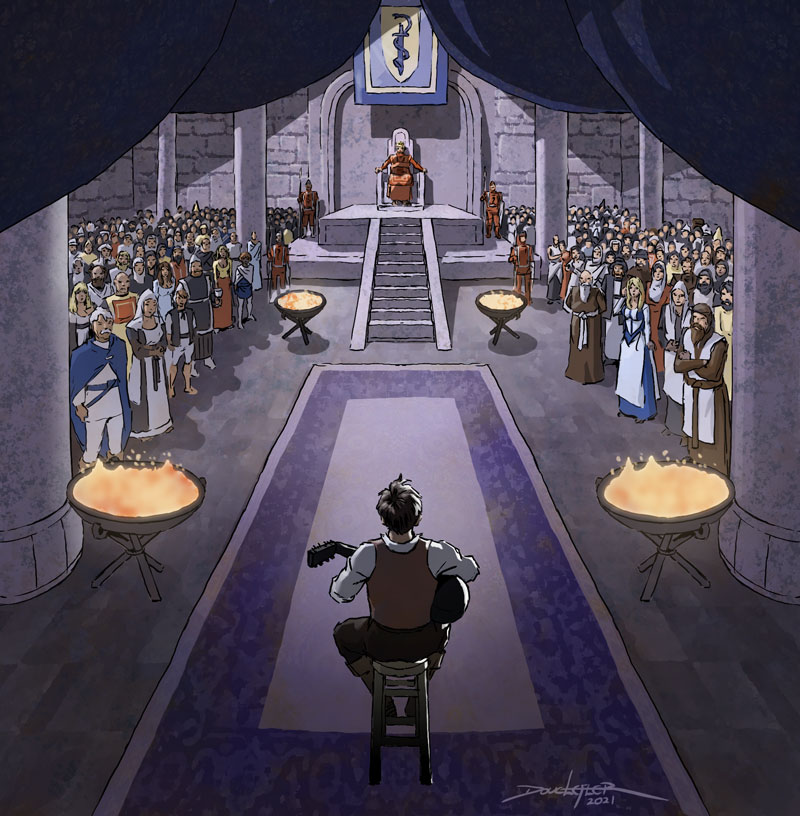

Bryn had never been inside a castle before. He had never seen a room with a ceiling so high as the Great Hall of Ironhorn. Rooms this spacious were difficult to heat, but the fireplace at the North end of the Hall was big enough to park a coach and four inside it.

Never had Bryn tasted venison or falcon-caught pheasant in a stew flavored with saffron and ginger. Never had he played to an audience that wore so much silk and velvet. When his hour came to perform, Bryn did not falter. The Minstrel found his voice and played as he had never done before. He thought about his indulgent father and long-suffering mother. How proud they would be if they could see him this evening. His thoughts wandered to “The Gryphon of Calamity,” the song extolling the adventures of the Three Huntsmen, composed with a simple melody and straightforward lyrics by the current Minstrel to the Court of King Edryd. “I can do better,” Bryn thought as his eyes feasted on the glory of the Great Hall. “All of this could be mine!”

“King Edryd wishes to speak with you.” The purple-clad emissary had returned as Bryn conversed with a young lady in an embroidered red dress. “Would you please await him in the East Hall?”

“Well,” the lady in the red dress raised an eyebrow and smiled at the Minstrel. “You mustn’t keep our King waiting.” She gave Bryn an elegant curtsy and turned to rejoin the mingling crowd. Bryn guessed the purpose of this meeting. The position of Court Minstrel was all but his.

The bear stared down at Bryn with unmitigated ferocity and unsheathed teeth. It was the largest bear the young man had ever seen and certainly the closest he had ever stood to one. The emissary closed the door to the East Hall behind him, and Bryn knew that he was trapped inside with this redoubtable creature. But the bear did not lunge. It remained frozen in its rage as if by a spell, with eyes unblinking and lifeless. Bryn glanced beyond the beast to see other creatures in the room, all locked in life-like poses but with vacant eyes.

“Are you familiar,” asked a cultured voice, “with the modern science of taxidermy?”

Bryn turned to find King Edryd behind him. The Minstrel bowed as low as he had ever done in his life.

“Oh, please,” the King motioned him to stand. He was a tall man of advanced years with a short, cropped beard and a walking stick inlaid with gold. “That’s hardly necessary outside of the Court.”

“If you please, your Majesty,” Bryn gestured to the bear. “How is it done?”

“The craftsman makes an incision in the slain animal here,” King Edryd raised his walking stick and pointed to a spot just below the chin of the bear, “it runs from the throat, down the belly to the groin.” he traced the path that the blade had made. “The skin is carefully removed along with the skull, paws, and feet. Everything else is extracted, muscle, skeleton, and innards, and precisely measure so that a framework of wood and papier-mache can replace them. The brains are spooned from the skull, and the eyes are replaced with glass. The results are as you see in this room. Look over here.”

Bryn followed the King to a raised platform that held a vast feline creature with a prodigious head made more imposing by a thick mane of hair about its neck.

“Is it a lion?” Asked Bryn.

“Very good,” replied the King. “All the way from the Dark Continent. We kept the creature alive until it got here so that it would be fresh. I intend to open this Hall to the common folk every other Tuesday so that the people – the tradesmen, the women, the little children — can marvel at my collection.”

“It may give some of them nightmares,” Bryn smiled but immediately regretted this attempt at humor.

The King paid no attention as he walked about the Hall, waving his stick like a showman.

“Taxidermy is a way of preserving the wonders of the Natural World. It is not unlike what you do in song.”

“How is that, your Majesty?”

“You capture a moment, a story, a feeling – in rhyme and melody. And if the song is good, it will outlast us both.”

“This is true, your Majesty,” Bryn agreed. “In my repertoire, I have songs that were written in the long-demised Court of Zarmyth, over two hundred years ago.”

“Ah, young man,” the King enthused. “You begin to see why I invited you here.”

“You want me to write songs about bears and lions?” Bryn asked.

King Edryd dismissed that idea with a wave of his stick. “What, this? No. Preserving the Natural World is something for the peasants. Merely practice for what truly matters. Come with me!”

When the King threw open the ornate double doors, Bryn realized that the room with the bear and the other dead creatures was a mere antechamber. The Hall they entered had to be much grander, for a dragon stood in the middle of it.

“My passion is preserving the wonders of the Fairie World,” King Edryd announced.

Bryn entered the room with a mixture of awe and apprehension. The Dragon towered above him with leathery wings half spread as if it was about to take flight. Its fiery scales were like a suit of armor, causing Bryn to wonder how anyone had managed to kill such a thing.

He looked about the room. A mermaid floated in a tank of yellow liquid, staring back at Bryn with her glass eyes. A unicorn had one hoof raised and its golden horn lowered, suspended in a moment before making a charge. There were Ogres and Leprechauns, Goblins, Hop-Goblins, and Gnomes. Protected under glass was a collection of fairies and a Phoenix Bird. In the middle of the room beyond the Dragon was a Cyclops and a Minotaur. Bryn identified the fabled Gryphon of Calamity, its wings spread in flight, hanging from chains attached to the rafters. There were Fauns and Werewolves and a Basilisk, and countless other creatures that Bryn could not identify.

“What do you think?” asked the King.

“It is awe-inspiring,” the Minstrel felt the need to pick his words carefully.

“And almost complete,” insisted the King. “Of course, there are many variants of Pixies and Elves that I don’t possess; but the only critical creature that I’m missing is a Hamadryad.”

Byrn’s heart pounded in his chest. “They are extinct, your Majesty.”

“Maybe. Maybe not. Your song “Lady of the Trees” is about one, is it not?”

“A work of fiction, your Majesty.”

“But it has the ring of truth to it.”

“Thank you. That was my aim.”

King Edryd took Bryn’s arm and led him toward the far end of the chamber. “Inspiration works in mysterious ways. Perhaps you were visited by a Hamadryad and didn’t know it. Perhaps in your sleep, or as you wrote, ‘passing through Old Badger Woods.'”

Dammit! Why did he add those lyrics to the last verse? “I suppose it’s possible, your Majesty, although unlikely.”

“If so, you are lucky to be alive. Hamadryads are cunning and dangerous creatures.”

“Are they? I heard they were passive and wouldn’t even protect themselves when threatened.”

“Balderdash!” The King snorted. “Old wives’ tales. I have it on authority that a Hamadryad once destroyed the entire village of Mer for the cutting of a single tree. My knowledge in these matters is extensive. For that reason, I outfitted the Huntsmen with the latest weaponry when I commissioned them.”

“The Huntsmen?” Bryn asked.

“Of Craggulch,” the King explained. “They are searching Old Badger Wood now.” King Edryd had led Bryn to an open platform at the far end of the Hall. “If they find one, my life’s work is complete…”

An inscribed metal plaque attached to the platform read: ‘HAMADRYAD.’

“…and the only necessity remaining will be the writing of songs.”

The King turned to smile at the talented young Minstrel, but Bryn was no longer there.

Fellow was an old horse, but he seemed to understand his master’s need for haste. Bryn was surprised by the animal’s capacity for speed. Did Fellow sense that the Hamadryad was in peril? As they raced over the rolling hillside, the castle of Ironhorn diminished behind them, along with Bryn’s chances of being a Court Minstrel.

The tug of war inside Bryn was over. Only one chain remained, and it pulled him in the direction of Modesty. His best hope was to reach her before the Huntsmen did. The two of them could escape together, find another forest. If the Huntsmen had already captured her but she was still alive, the situation was more complicated. He had no martial training and had not been in a fistfight since he was eleven, and he lost that one to the Tinker’s son. What could one skinny lad of nineteen do against three burly men who killed things for a living? If they had already found her, but she was no longer alive – Bryn refused to contemplate that scenario.

“Where do you suppose she got the shirt?”

It might have been Malwyn who spoke. Bryn felt a tension in his stomach when he heard these words. The only light in the birch grove came from the three Huntsmen’s campfire. The Minstrel had left Fellow beyond the bend in the forest road, and he hoped his horse wouldn’t follow him. Bryn stepped through the darkened undergrowth on weak legs. He had saddle sores from making a two-day journey in a day and a night, and he ached from every part of his body.

“Doubtless, she stole it from a traveler’s camp,” it was probably Mervyn responding.

“Are you both blind?” Madog asked. “It’s the shirt that minstrel wore the night we met him.”

Bryn was at the edge of the camp. The firelight cast expansive shadows of the Huntsmen across the grove. The draft horses were on the far side of the clearing, upwind from him.

“…he probably gave it to her.” Madog continued. “And was hiding her from us the whole time.”

“Not a lot of good it did in the end,” Malwyn said with a glance at the figure dangling from a large elm tree at the edge of the camp.

Bryn felt his heart go from a canter to a gallop when he saw Modesty’s limp form hanging from the rope. Leather bindings secured her wrists and ankles. There was no sign of breath in her body as it slowly rotated in the night breeze. When she was facing him, he leaned forward. Her eyes flashed open, and Bryn almost fell backward. She was alive! He put a finger to his pursed lips, motioning her to be quiet. She pursed her lips back at him accusingly as if to say, “YOU be quiet.” Of course, the Hamadryad could move through the wood in perfect silence, but Bryn – he was a village boy.

As Madog and his brothers busied themselves with their supper, the Minstrel slipped the knife from his belt and stepped halfway into the firelight. It was not a formidable knife since its primary function was whittling wood and slicing bread, but it was equal to the task of sawing through the straps between Modesty’s ankles. The knots around her wrists presented a more profound challenge. Even if he stepped fully into the light, he would not have been able to reach them.

“I told his High-and-Mightiness that we weren’t needing all them crossbows, chain mail, and chariot spikes,” Mervyn said with a mouthful of salted mutton. “‘A long pole with a noose on it is all I’ll need,’ I told him. And was I right, or was I right?”

Bryn motioned to Modesty that he would circle the camp and climb into the tree. She looked alarmed, glanced at the Huntsmen and back at Bryn, and shook her head. The Minstrel shrugged in reply. There was no other option.

“I admit,” said Madog. “I was expecting more of a fight from the likes of her.”

Bryn tip-toed to the elm tree. He was closer to the horses than he wished to be, but there was nothing for it.

“The question now is, can we get her back to Ironhorn alive,” mused Madog as he drank from a jug of Honey Mead.

The Minstrel slipped the knife between his teeth and prepared to climb. He quickly reconsidered, took the knife from his mouth, and put it back in its sheath.

“You expect her to resist?” asked Malwyn.

“The King don’t think she will live long once we removed her from her trees.”

Mervyn wiped his mutton greased hands on his tunic. “She’ll still be fresh enough, I reckon.”

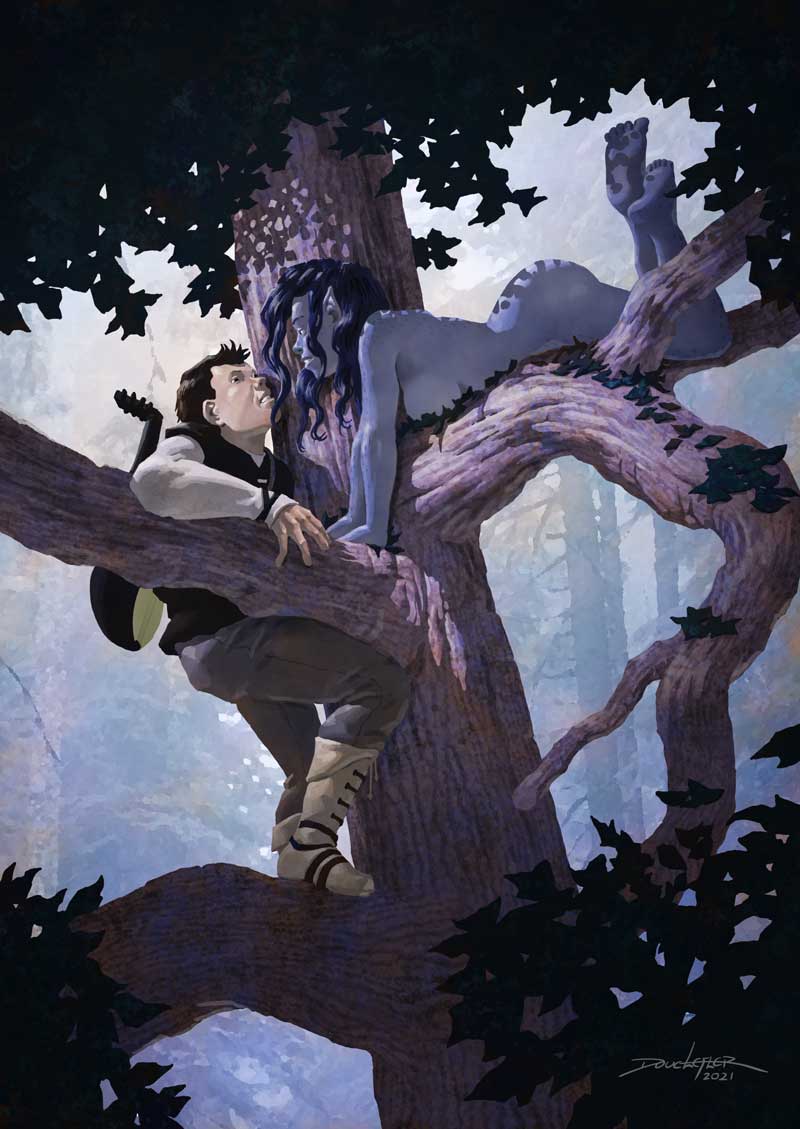

Modesty’s eyes surreptitiously followed the Minstrel’s progress up the trunk and out along the branch. He was in full view of the fire, but no one was looking up just now. The Huntsmen’s conversation turned to game and cockfights as Bryn reached the knotted ropes, redrew his knife, and commenced sawing.

Strand by strand, the rope gave way. If he had the foresight to sharpen the blade before he came, this escape would have gone faster, but the business of adventuring was new to him. All at once, the line snapped free. Modesty dropped to the ground without a sound, but Bryn’s knife slipped from his hand and fell after her.

“Look out,” he warned in a clenched whisper.

Modesty easily evaded the blade, which impaled itself in the ground next to her bare feet.

“Hey there!” Madog shouted, spitting mutton into the fire where it sizzled angrily. “She’s loose!”

They had lost the advantage of secrecy.

“Run, Modesty!” Bryn shouted, drawing attention to his location on the branch. The imperative was unnecessary as the Hamadryad had already vanished without rustling a leaf.

“Holy Hell!” roared Malwyn. “It’s the bloody singer.”

“You two find the girl,” Madog ordered. “I’ll get the Minstrel.”

Mervyn snatched up his long pole, and Malwyn took a crossbow. They rushed from camp in the general direction where they last saw the Hamadryad.

Bryn heard Madog coming for him, and his first thought was to climb higher. But he was too slow and the Huntsman too tall. The Minstrel felt his foot grabbed, and the next moment he was flailing through the air to land gracelessly on his back. The wind left his lungs. Madog was on top of him; one big hand pinned Bryn to the dirt.

“And after we shared bread with you! There’s gratitude!” the Huntsman spit. “That animal was our fortune.”

“She not an animal!” Bryn’s anger overcame his fear, and he kicked one of his legs up to catch Madog on his bearded chin. The impact was negligible to the Huntsman, who drew his hunting knife and placed it at the young man’s throat.

There was motion in the tree above. Modesty landed on the Huntsman’s back and gripped his knife-hand.

“I told you to run!” Bryn cried in alarm.

Madog pivoted in a crouch and slammed the Hamadryad to the forest floor.

“Boys!” He called to his brothers. “She’s here. She never left the camp.”

Madog lifted the knife to stab the Hamadryad. Bryn rolled free, grabbed a burning log from the fire, and crushed it across the back of the Huntsman’s head. It was a solid blow, and the big man pitched forward. Bryn had never knocked out a man before, and now he had no time to appreciate the accomplishment. He pulled Modesty to her feet just as the other two Huntsmen reappeared.

The horses stamped in alarm. Malwyn pointed the crossbow at Modesty, but Bryn stepped in front of her with his arms wide. The impact of the bolt hitting his shoulder lifted the Minstrel off his feet. He landed on the ground beside the girl that he had come to rescue.

The crossbow is a formidable weapon, but it is slow to reload, and at this moment, it would be salient to observe the danger that comes from having insufficient knowledge of your prey. For it was accurate that the Hamadryads would not defend themselves in the face of their own demise, but their ability to protect the things they love, be they trees or Minstrels, was terrifying.

From his position on the ground, Bryn saw Modesty’s eyes glow an aggressive red. She screamed as she dropped to her knees and clawed her fingers into the earth. The ground rippled outward from her hands, and the trees replied. Roots erupted from the dirt. Branches descended from above. Before Malwyn could replace the bolt on his weapon, he felt sharp wood pierce his chest to find his heart. Mervyn dropped his long pole as a branch wrapped his throat and gave his neck a decisive snap. Roots enveloped Madog’s unconscious form and crushed his spine.

Before Modesty finished her scream, the Three Huntsmen of Craggulch were dead. The echo of destruction rumbled through the Old Badger Wood, and every forest creature heard it.

Bryn looked up at the Hamadryad as her rage abated, and the red glow left her eyes.

“Modesty?”

His mind was dazed and his body in shock.

“Quiet,” the Hamadryad said. “Rollover.”

She gripped him by his uninjured shoulder and helped him onto his stomach.

“Did you just speak?” The pain from his wound was asserting itself. Modesty held him down with a knee on his back. The bolt was protruding from his shoulder, and she took hold of it just below the barbed tip.

“Hold still,” she said and yanked the bolt free by pulling it through from the other side.

“I’m sorry I didn’t come back sooner,” Bryn said as the Hamadryad dressed his wound with thin strips of bark over a poultice of meadowsweet, silverweed, mistletoe, and several herbs that were unknown to the Minstrel. The dressing eased his pain, but the touch of her hands seemed to have the most salubrious effect upon his wound. “None of this would have happened.”

“But you did come back,” Modesty replied.

“When did you learn to speak?” He had to know. “And why didn’t you do it before?”

“My kind is slow to trust,” she said and kissed him gently on the forehead. “If you stay with me, I can teach you many tongues. Would you like to sing in the language of the trees? You could serenade the river reeds or hum rhythms that only the stones can hear? If you know how to ask it politely, the wind will carry your melodies to the far corners of the world. Come with me, back to Whispering Hollow, where no mortal man can find us if we don’t choose to let him in. Bring your lute and your horse. I will answer all of your questions.”

“Do you have a real name?”

“Many,” she kissed his mouth. “But none that I like more than the one you gave me.”

EPILOGUE

“A fine story and well told,” the Candle Maker said as he pulled on his pipe. “Except for the obvious discrepancy.”

The Storyteller had shouldered her lute upon its strap and was collecting her coins. The caravan of merchants began to abandon their campfire and wander back to their wagons. They were passing through Old Badger Woods to the New Conquest Market when they met the young woman. She offered to sing for them and tell them a tale. It was unusual for a traveling bard to be a young lady. She carried no weapons, and she may have been pretty, it was hard to see since she kept her hood on the whole evening. Someone could have easily robbed her — or worse — if it were not for the wolf.

“What discrepancy?” asked the Storyteller.

They were interrupted by the Milliner. “How much for a kiss?” he asked, holding a coin in one hand and a mug of Goodale in the other.

The wolf sitting on the ground next to the Storyteller gave a low grumble inside its cavernous chest. Its upper lip raised just enough to show a hint of teeth. It was sufficient to motivate the Milliner to drop his coin in the girl’s cup and stagger away to search for his cot.

“What discrepancy,” she repeated in a sweet voice.

“You say the story is true,” explained the Candle Maker. “And that the Minstrel followed the Hamadryad back to Whispering Hollow and was never seen again by the eyes of mortal men.”

“Aye,” the Storyteller confirmed.

“So, how do you know what transpired? The Huntsmen were dead, and there was no one else to pass on the story.”

“An excellent observation,” she replied. She patted the wolf’s haunches, letting it know that it was time to leave. The beast stirred and shook its great bulk. “You see, the Hamadryad had been the last of her kind. But her union with Bryn ensured that magic would not die in the world. Not yet at least –”

Here the young lady pulled back her hood so that the Candle Maker might see her lightly spotted blue skin and gracefully pointed ears.

“– for I was relating the tale of how my mother met my father.”

A moment later, both the girl and the wolf had vanished into the forest.

An excellent story. Thank you.

Thank you for reading it, Kevin.

Thank you for the story- it seems to be a promising vignette, a backstory for something more to come?

It’s possible, Richard. Stories have a way of branching and multiplying.

I enjoyed the story very much, thank you for it

Love your work

Thank you, Menny!