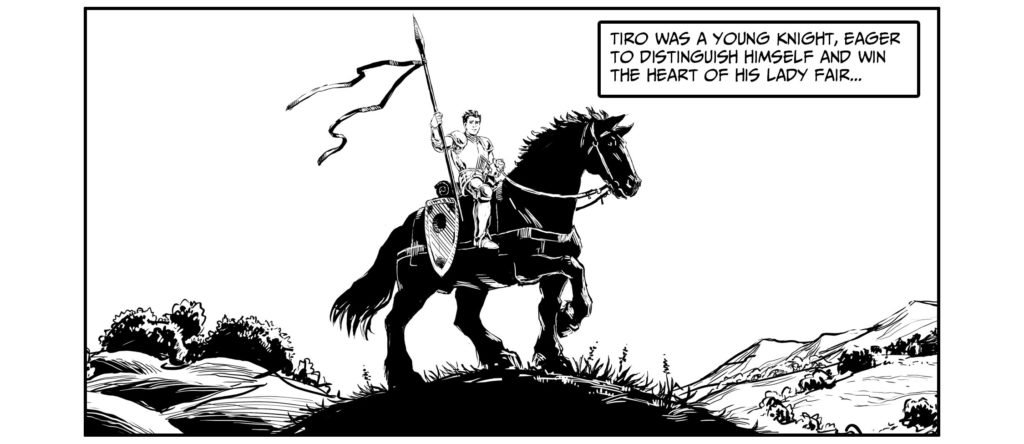

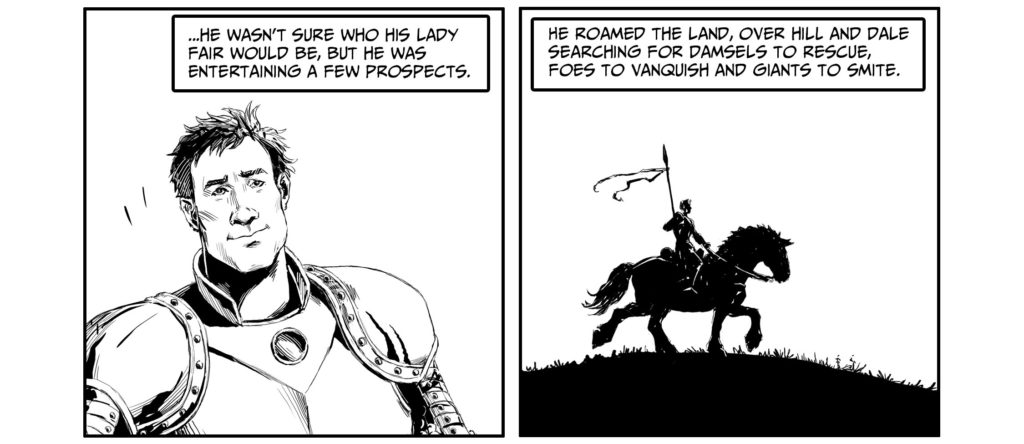

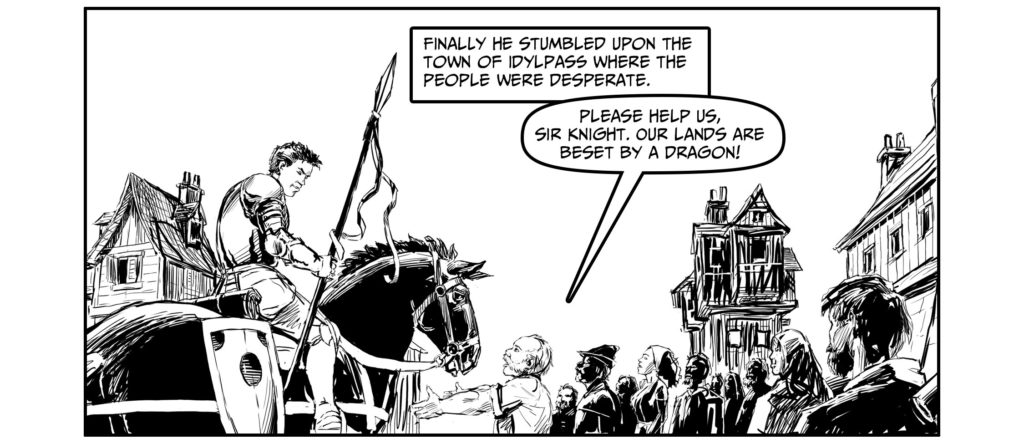

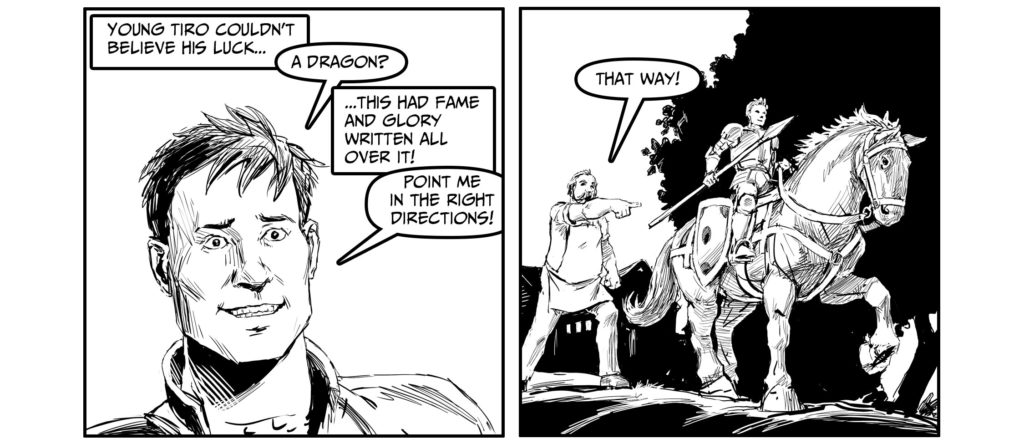

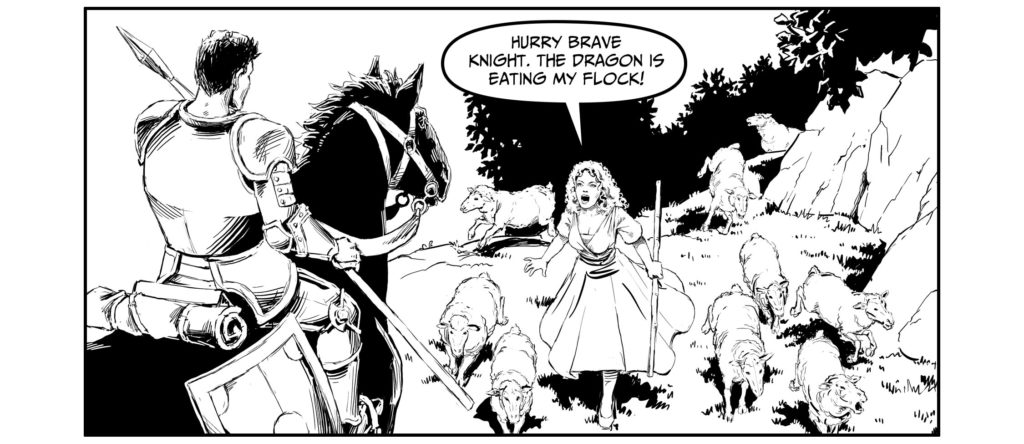

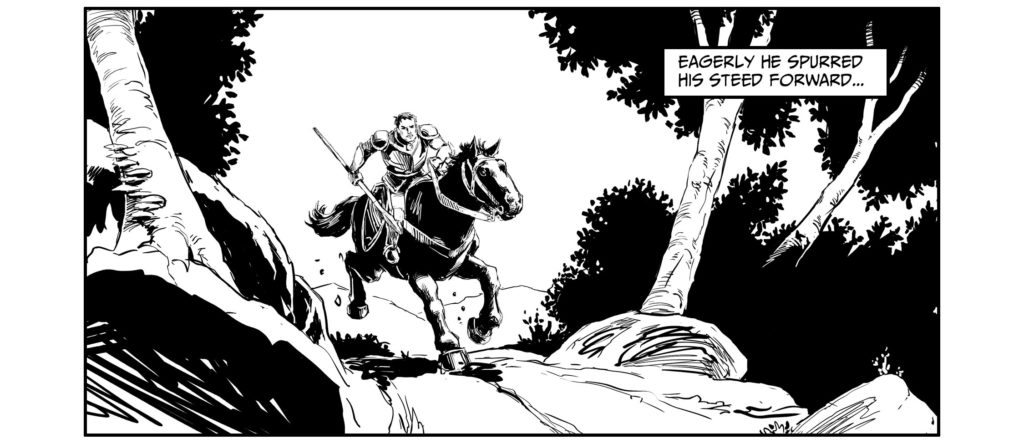

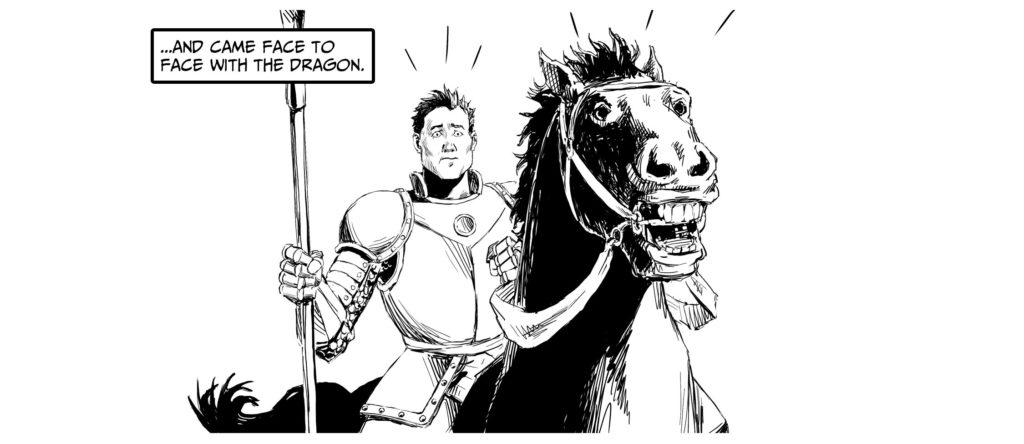

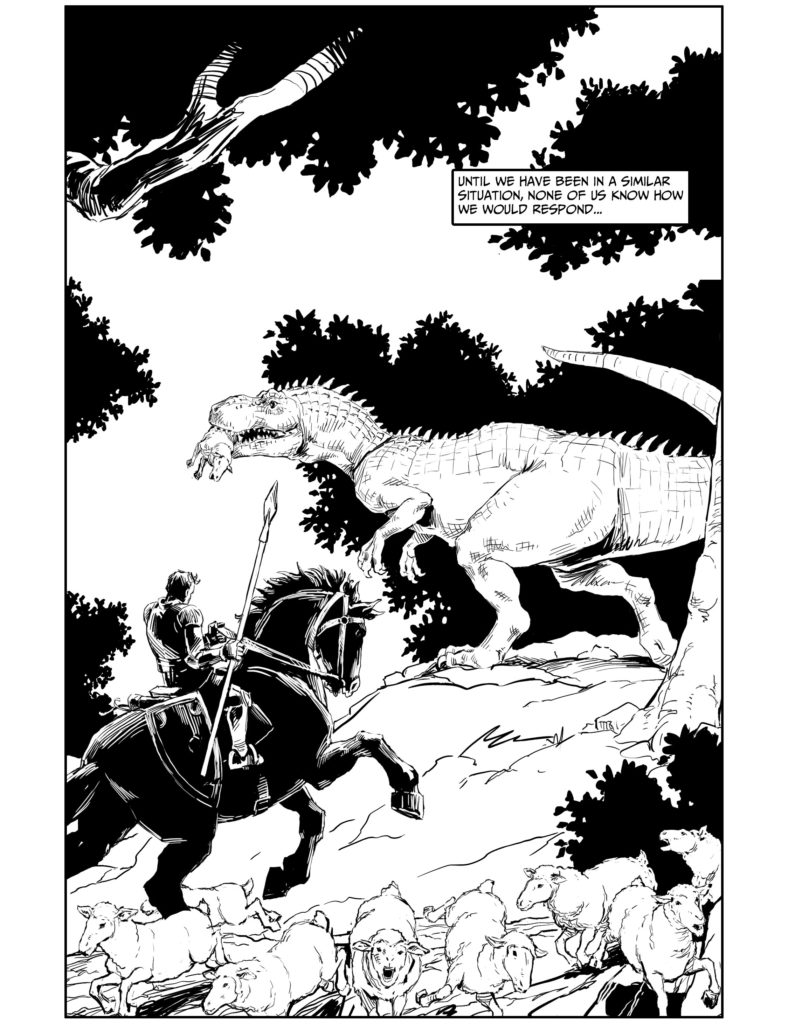

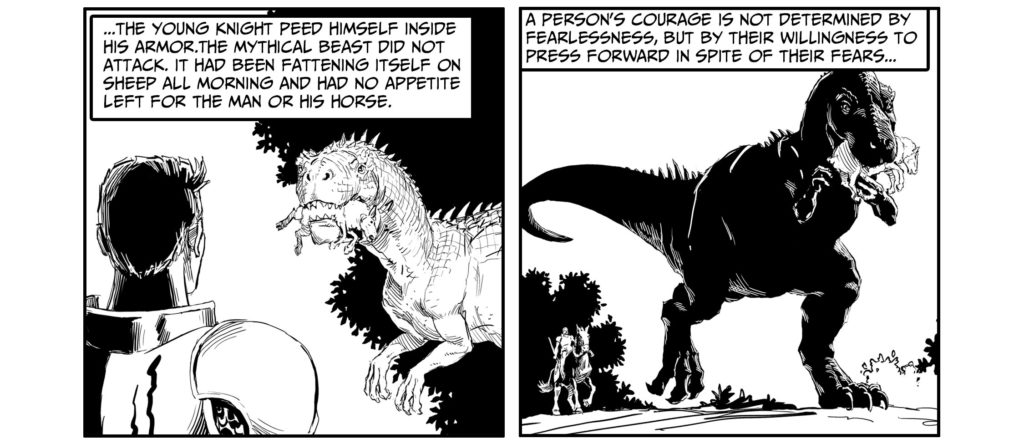

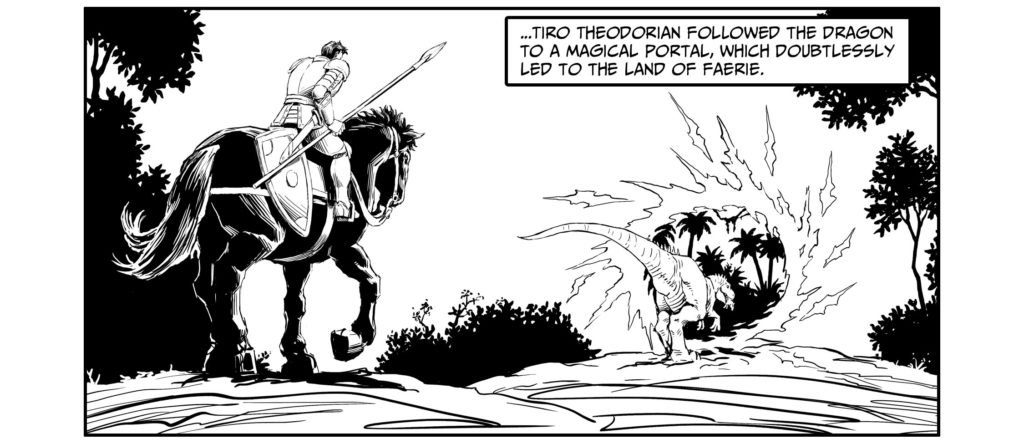

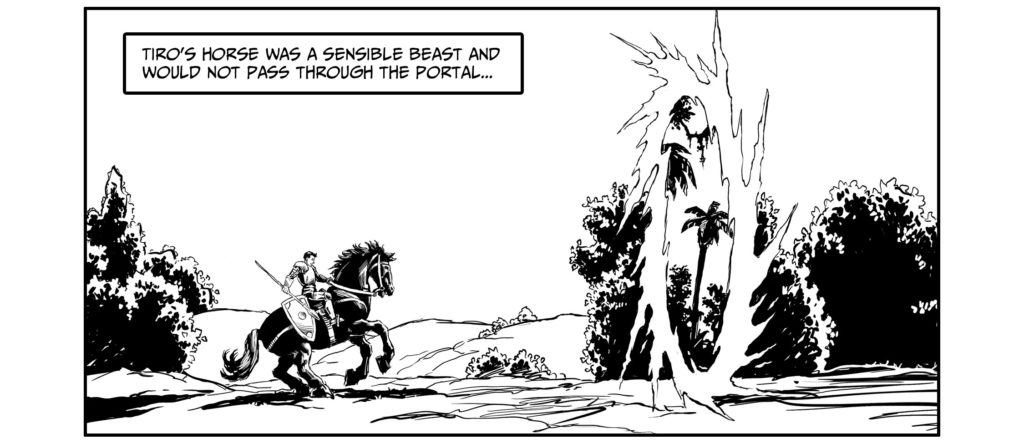

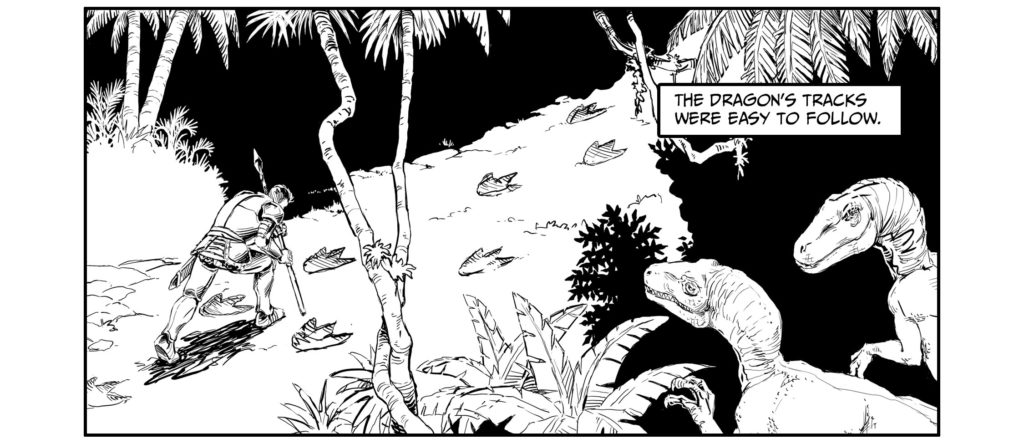

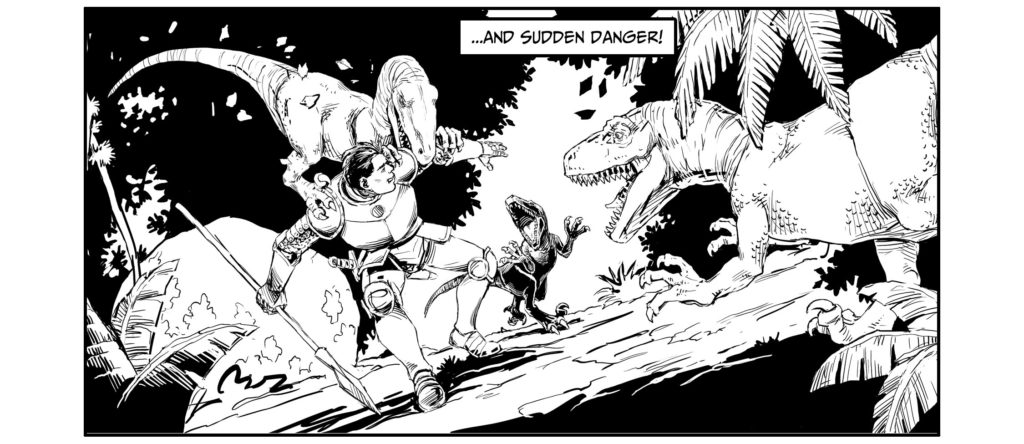

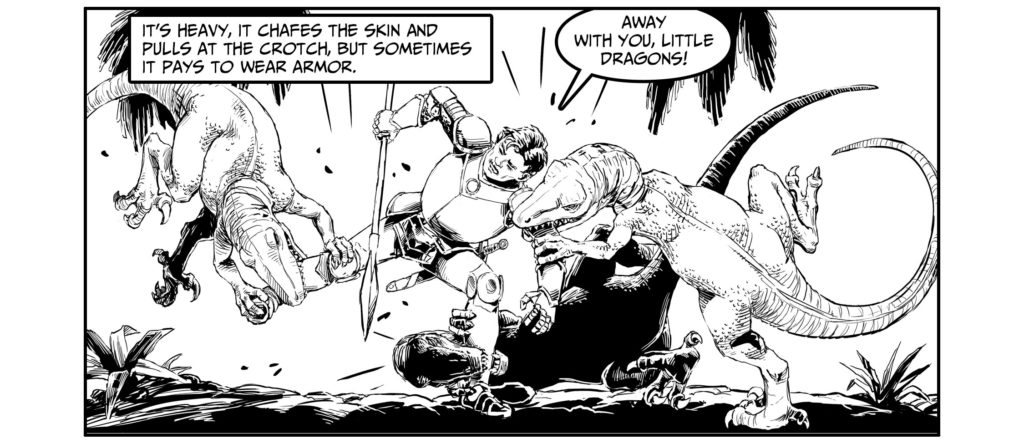

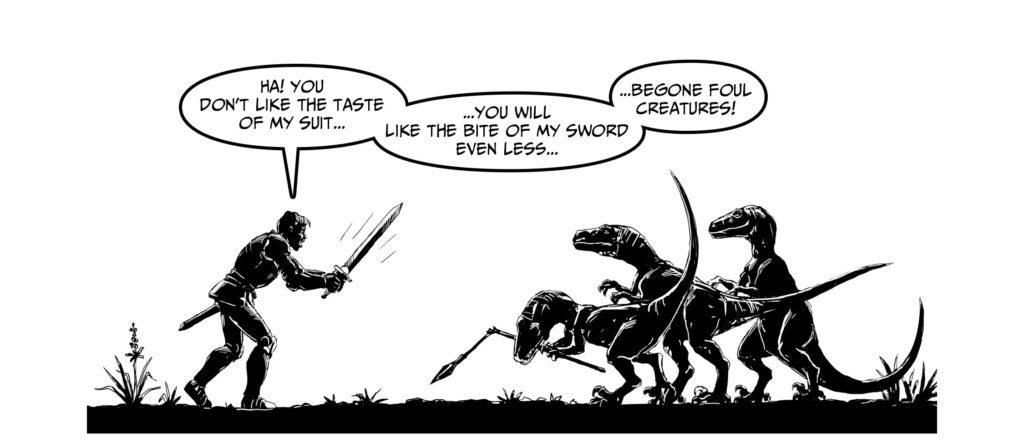

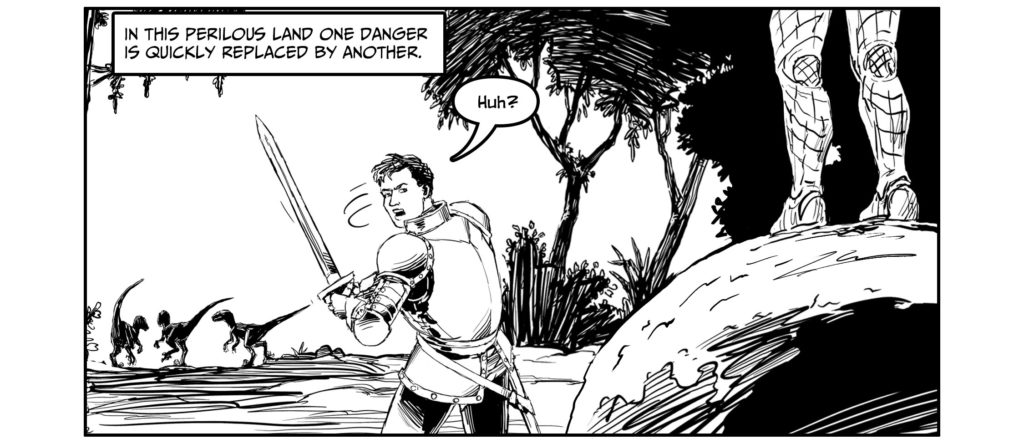

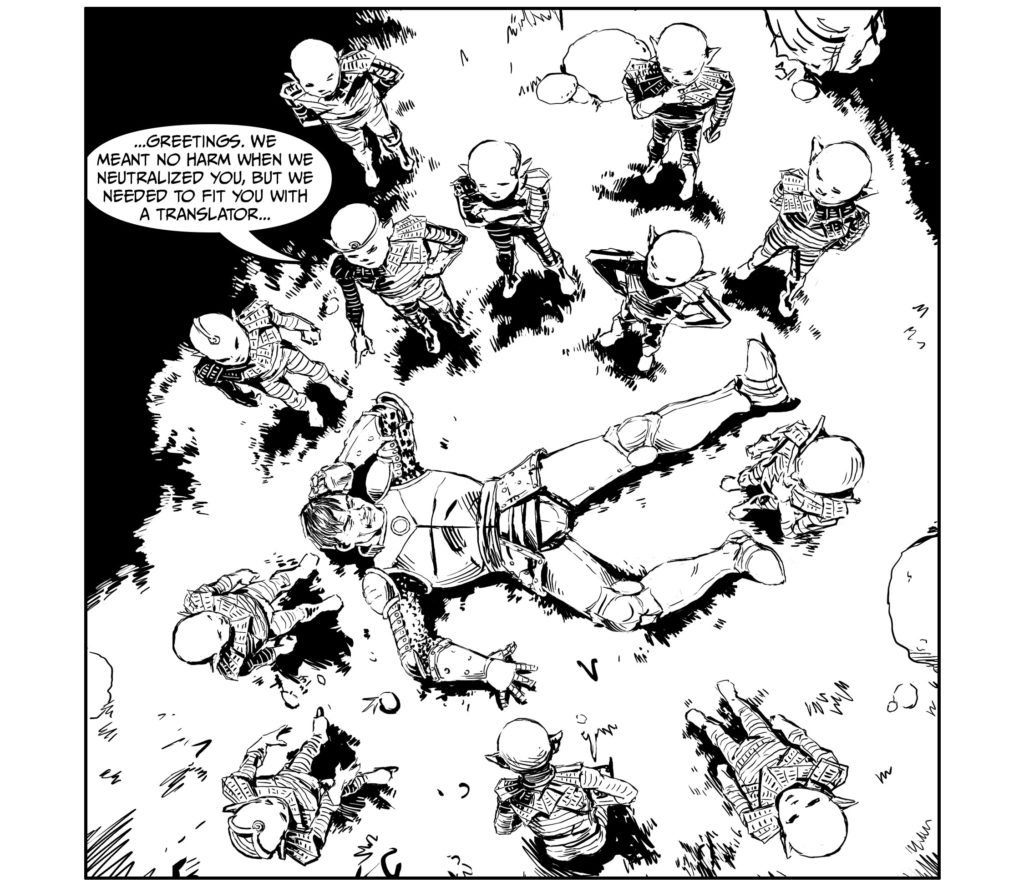

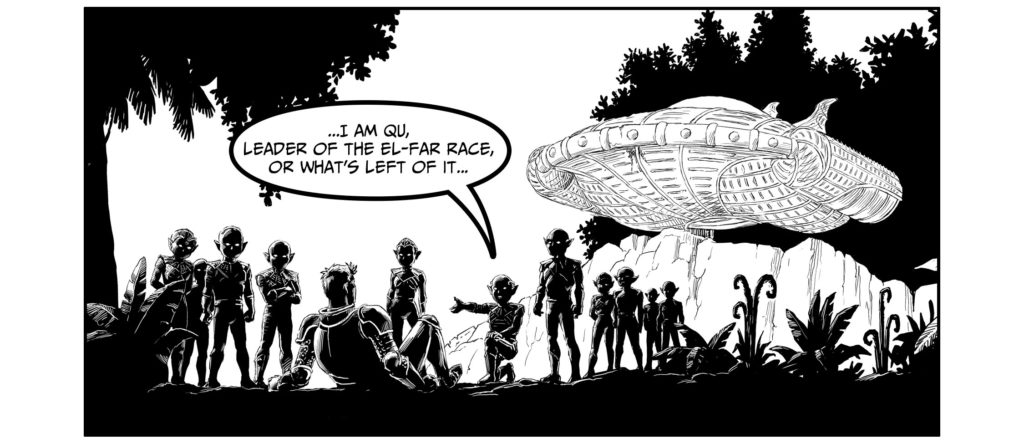

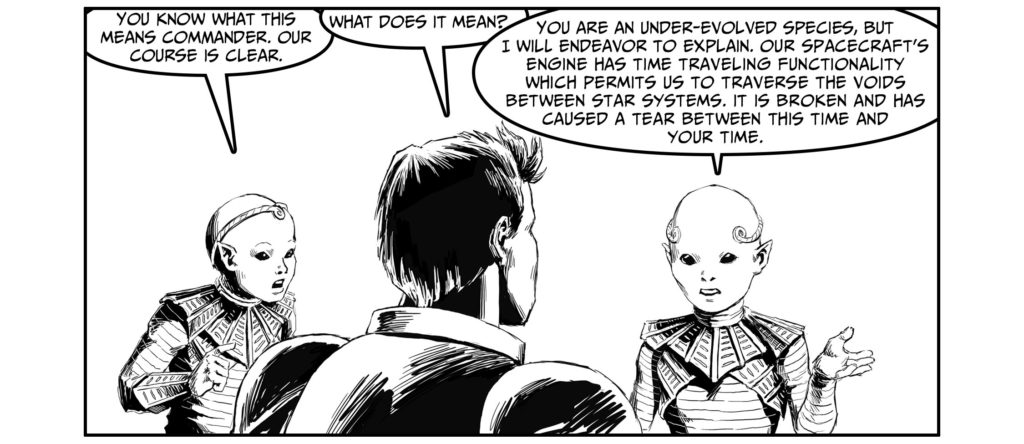

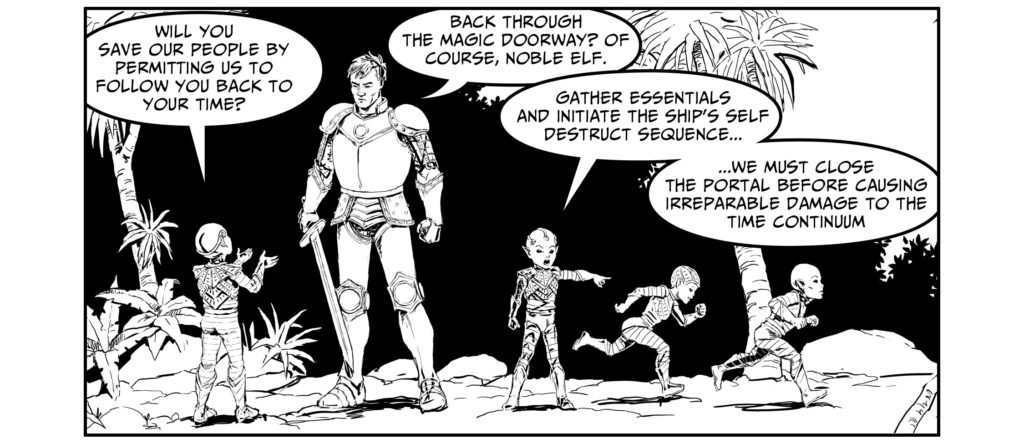

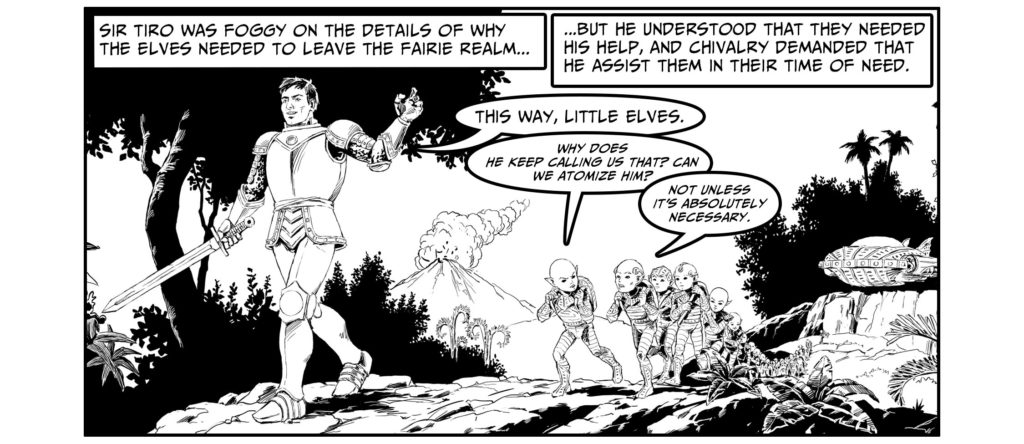

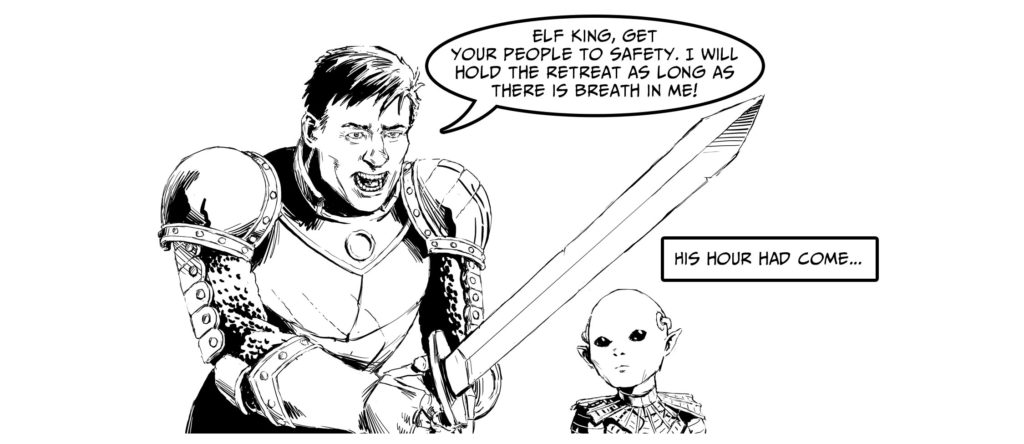

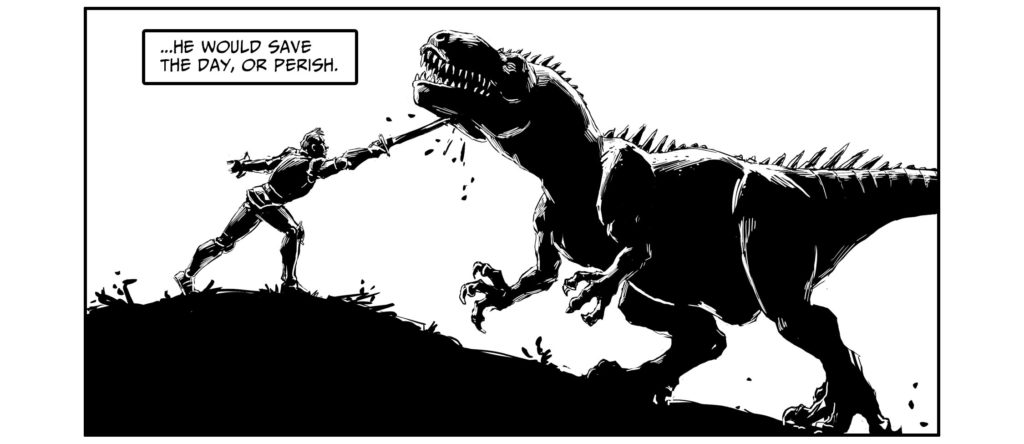

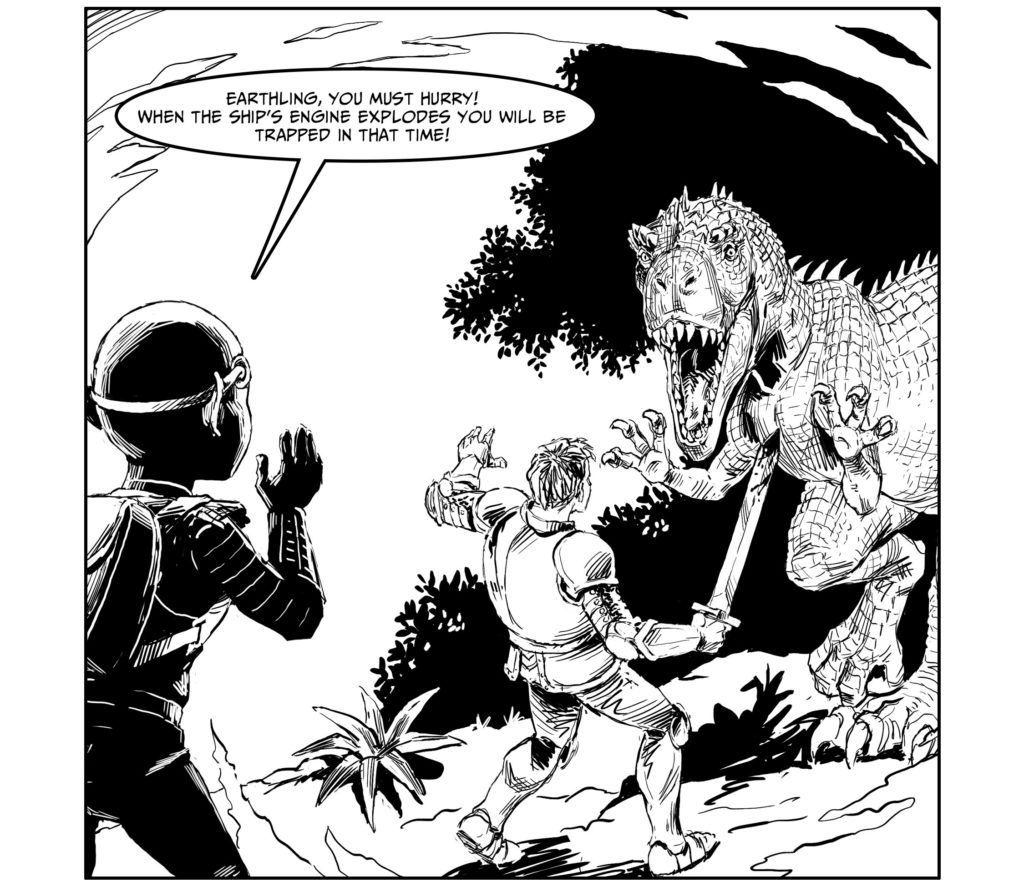

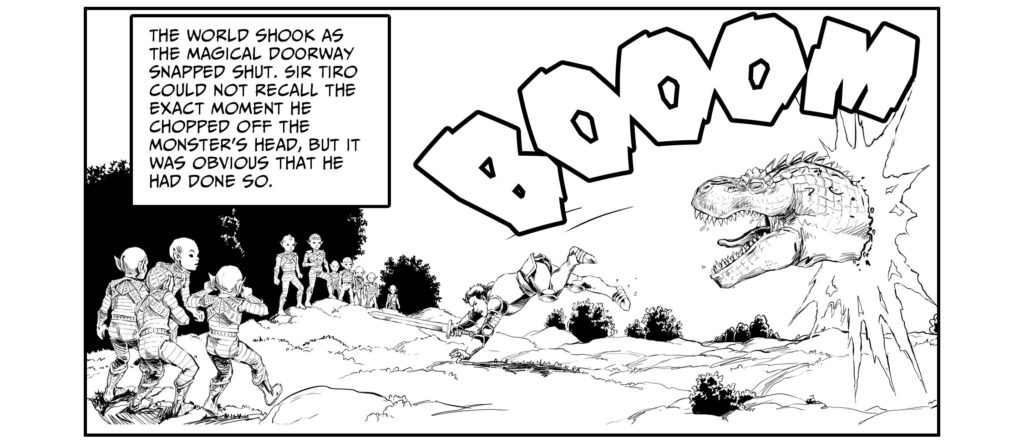

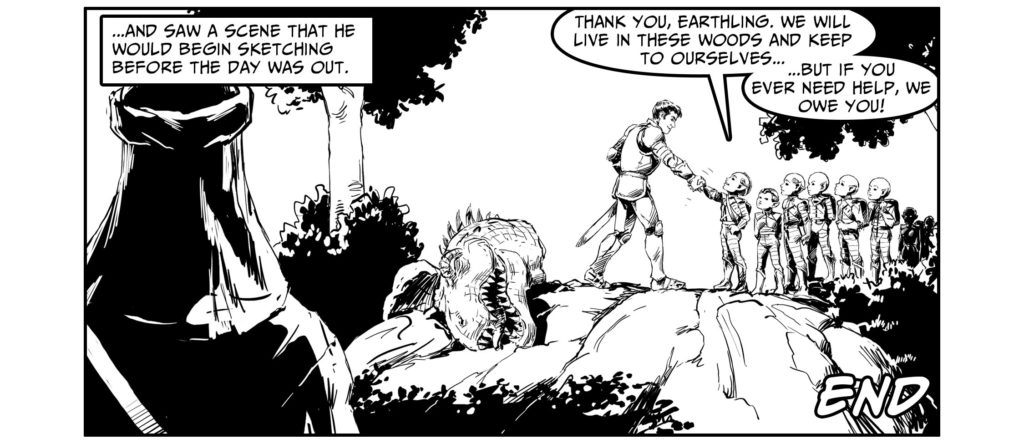

Sir Tiro sought to distinguish himself by slaying a dragon, but he had no idea where or when it would take him.

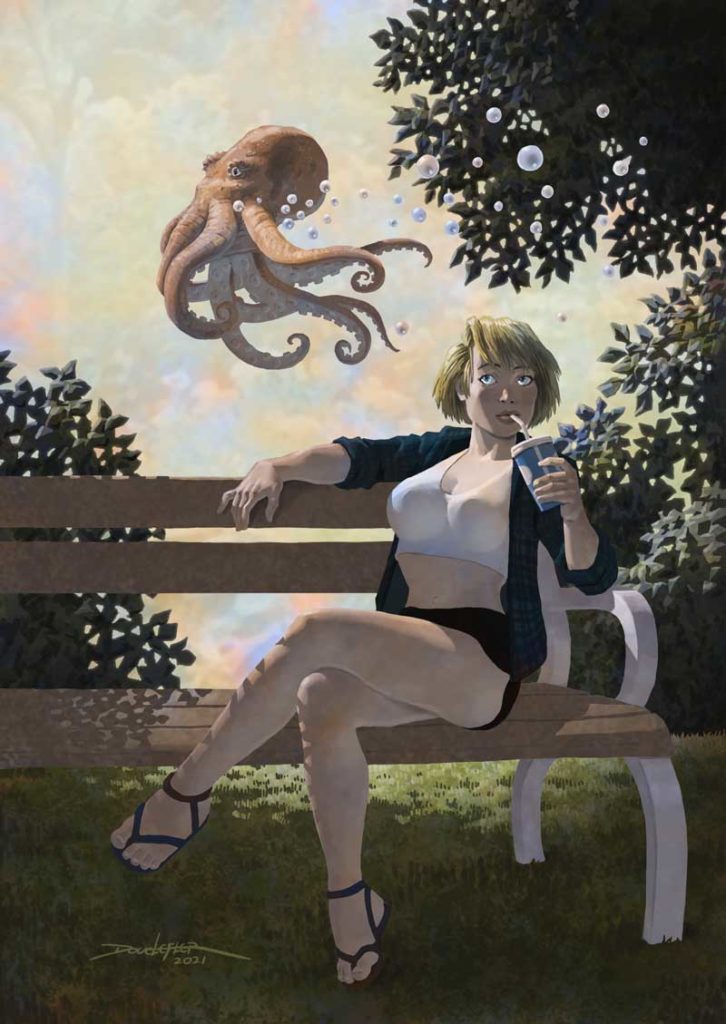

Last year I sketched and painted a lot of aquatic-themed pieces. At the beginning of the year, sea shanties were trending on TikTok. Some of them found their way to me and influenced my work process.

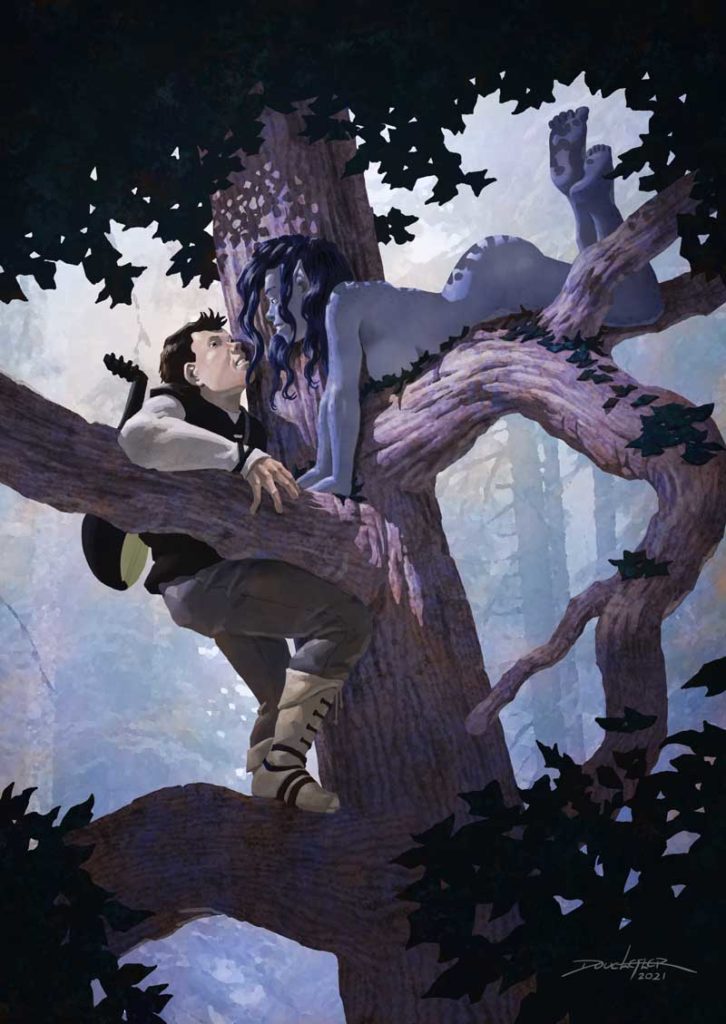

I am not a marine artist, but many a good adventure tale has begun with a sea voyage, and I have read all of the Horatio Hornblower books. However, I don’t recall Captain Hornblower encountering a mermaid during his travels, but I’m willing to forgive C. S. Forester for this oversight.

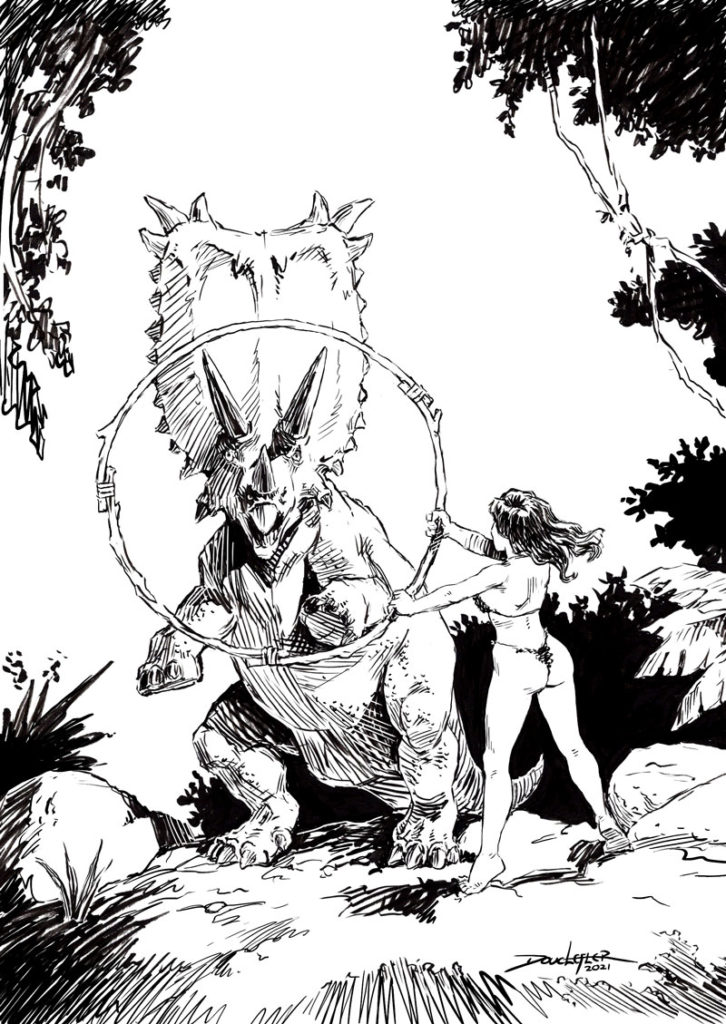

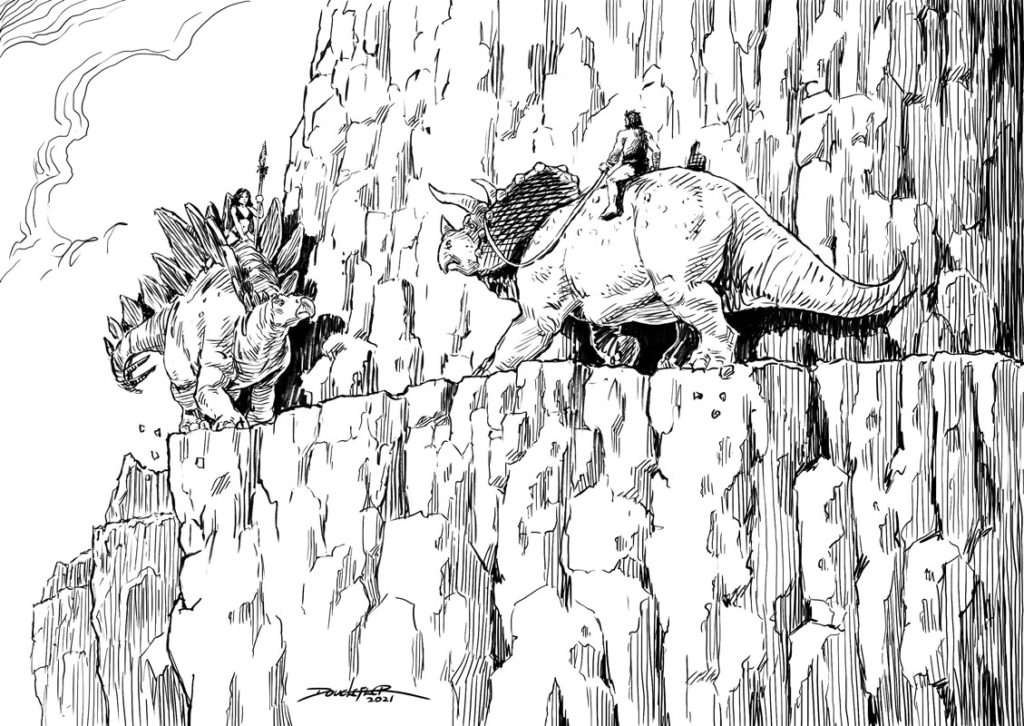

In 2021 I appreciated Frank Frazetta and Heinrich Kley‘s impact on my work. I wrote about meeting Frazetta, but more should be said about Kley. His work’s vibrancy, especially his animal drawings, significantly influenced Walt Disney. Early in my career, one of the older Disney artists (it might have been Blaine Gibson) told me that Walt wanted all his animators to draw as well as Kley, but nobody could.

Heinrich Kley was a German illustrator who made his living painting industrial scenes beginning in the late 1800s. Then, he started drawing funny, outlandish, and occasionally risqué images of nymphs, monsters, and animals to amuse his new bride. These sardonic drawings brought him the most notoriety, but he faded into obscurity during Hitler’s regime. The Nazis put him on their “List of Harmful and Unwanted Writings.”

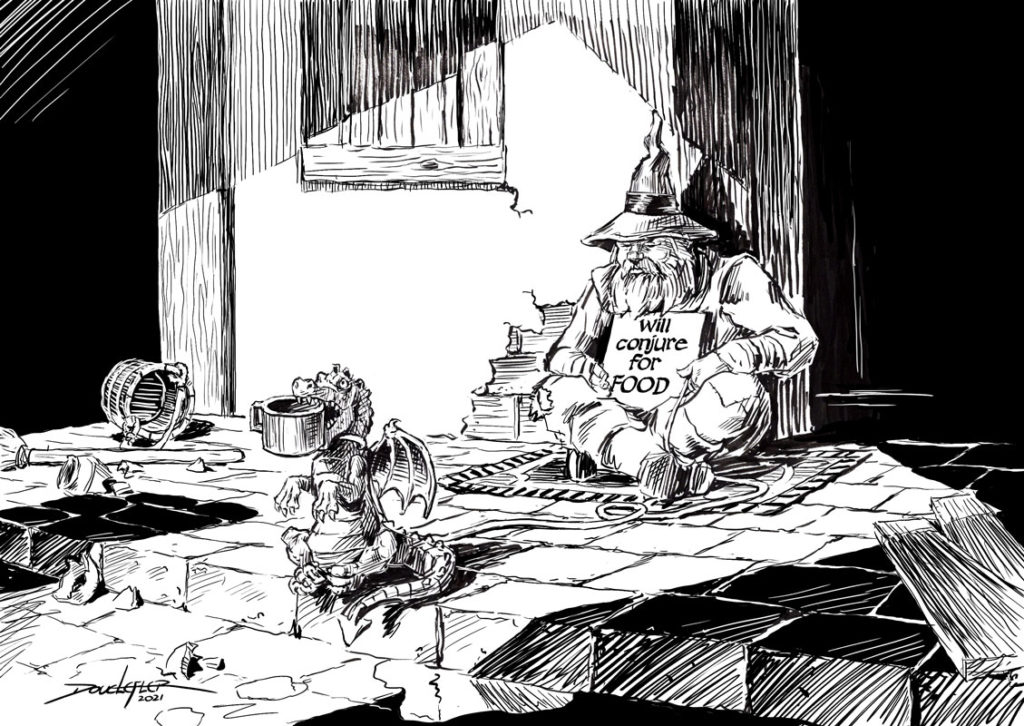

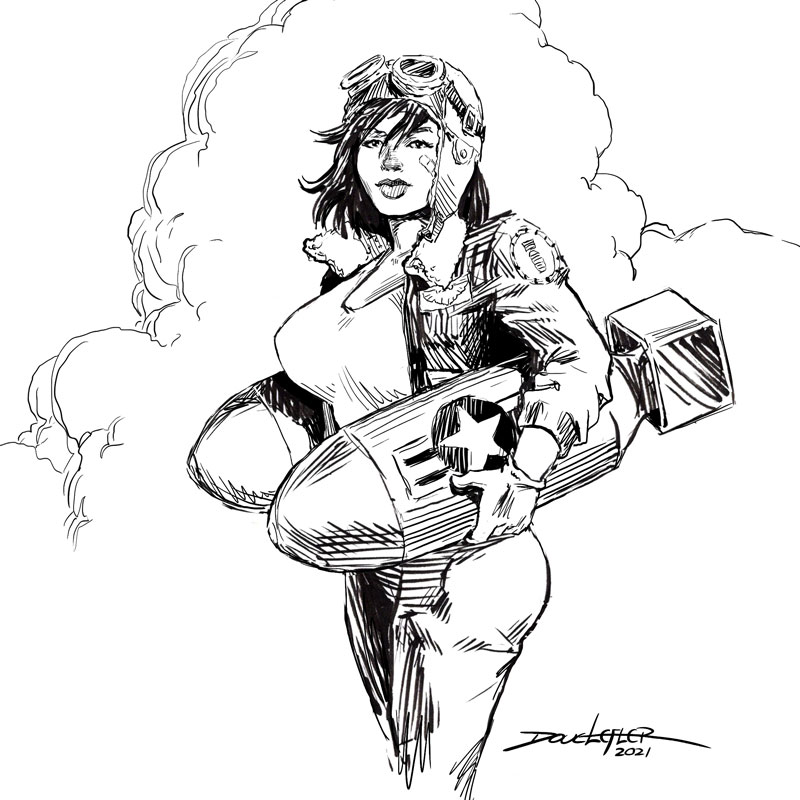

I don’t think a lot before I start to work, but I like using animals and robots to convey human emotions, almost as much as I like to draw women and children with dangerous pets. And from time to time, I have been known to sketch the female figure for its own sake.

Take time to appreciate the small but extraordinary things that happen around you every day.